Insights are scary

During a recent tour as strategy chief at a holding company agency here in New York, I was presenting a proposed strategy group work model to the senior team. About five minutes into my presentation the head of office asked me, “What do you see as the primary job of the strategy group here?” Without hesitance I said, “Insight – that’s our product.” The MD and his executive creative director both nodded warily in agreement. But a longtime VP of strategy from my team meekly coughed and said, “Actually, I don’t spend much of my time developing insights.”

Weirdly, we were both right. In an ideal world, a strategist’s job is to plumb the depths of the human condition with research, and come up with insight. In the actual world, strategists spend most of their time picking existing insights from the shelf, dusting them off to develop briefs, plans and customer journeys.

Thirty plus years of doing strategy suggests two reasons for this. The first reason is that insights, at least the job of finding and naming them, scare people. The good ones, the deeply actionable ones, are hard to find. Having insights production in your job description can stress a strategist’s day. Better to focus on the more easily observed analysis of behavior and tastes when designing products and writing briefs, as it’s rare to be fired for reusing old insights. The second reason is money.

Insights are expensive

It takes time, people and resources to do the questioning research needed to wander the realms of human desire in search of fresh insights. If you’re a brand or product manager you decide if, when and how much to invest in research that is never cheap and usually threatens to take longer than you think you can afford to wait.

Then there’s the result, the product of our research, the insights your brand can do something with to drive the business. There’s only one way a marketer can calculate whether their investment in insights was worth all this effort, time and money – put those insights to work. You’ve got to brief, plan and design stuff with them, and then measure their ability to create meaningful value.

You had one job

I teach five different marketing and business courses in two universities here in New York City. there’s a single slide that shows up early in every one of those courses and it looks like this –

Years of doing this stuff around the world and across every category have taught me this: marketing has one brutally simple job, transforming human insights into business value. Many more fails than wins has also taught me if you get consistently good at pulling off this formula, the business you’re working for becomes extremely difficult to compete with.

This insight about insight lies at the heart of the business case to be made for investing in – and then doing something meaningfully with – fresh, deep insight.

Methods matter

Insights can come from anywhere, but mostly they come from research. For true insights geeks, traditional research methods like qualitative focus groups or quantitative surveys have lost their ability to uncover fresh, deep insight. We almost always are never surprised, and this shouldn’t surprise us. We’re stacking the deck by design with research that asks people how they think, feel, believe or behave.

Emergent research methods like deep listening and digital ethnography are more likely to uncover fresh insights than any combination or type of traditional research. They are observational and largely unstimulated. We observe how people behave, what they say, how they treat each other. These observations become signals for how these people actually feel, what they believe, what they’re frightened of and driven by, what they want and need. The very stuff of human desire.

Deep listening – analyzing the contents of social conversational media – is one of the most powerful new methods of observational research. Its procedures and ethics are an evolution of the practices first developed by the pioneers of ethnography in social science, behavioral psychology and cultural anthropology of the early 20th century.

When combined in sequence with equally emergent digital ethnographic studies fielded via mobile video, we have something no generation of insight hunters ever enjoyed: a one-two punch research platform capable of leading the probative analyst to deeper insight into the human condition than they ever imagined.

The agency business case

Remember who’s talking here. I’ve been a hired holding company gun for much of my career, a strategy guy rented out to brands by his agency handlers. Marketing agencies don’t typically invest in producing fresh insights for their clients unless they get paid for it. Most of the time a consulting strategist like me works with whatever insight the brand gives us.

Over the past two years I’ve finagled modest budgets from my agency chiefs to develop fresh insight to inform our efforts to pitch new client business. In each case, the brand team gave us their existing audience insights to work with. In all three cases we applied a sequenced combination of deep listening and digital ethnographic research studies. In all three cases we successfully demonstrated the business case for fresh insights – by winning the account.

But the real business case for investing in fresh insight can only be made when we measure the result it has on the business who applies it to reimagine their marketing, their products, their brand or their very business itself.

The brand business case

The thread connecting the three cases below is the potential business value from pushing harder against existing insight until we break through to even deeper ones.

In each instance we started with the baseline audience insight the brand team briefed us with. We invested from $10,000 to $15,000 of people, tech and money in a sequenced research program of deep listening plus digital ethnographic. In each case we reported back to the brand team with two things they didn’t have before – a fresh insight about their audience and a creative strategy you get with a sharpened insight.

“Redlined”

The brand Capital One’s Platinum Card… The challenge was to suggest a fresh message and marketing mix for new customer acquisition. The audience insight they had been working with was time challenged, financially naive.

Deep Listening program We developed a linguistic and semantic taxonomy (expressed as boolean queries) to probe the social conversational ecosystem for evidence of human stress, behavior and feeling around all things ‘credit’. We articulated a mix of insights – ‘less than’, ‘left out’, ‘clueless’, ‘angry broke’ – and developed short descriptive territories to test in a digital ethno study.

Digital Ethnography program We recruited ~20 consumers within our product’s demographic cohort, all with claimed experience of financial anxiety from low credit scores. We asked each to respond via video, text and image to the territories we developed from the deep listening study.

The results We uncovered a fresh insight – redlined – revealing a self-alienated, stressed-out human, approaching the end of hope for sorting out their financial lives. The creative strategy and platform we developed with this insight was a new democracy of credit for people like us.

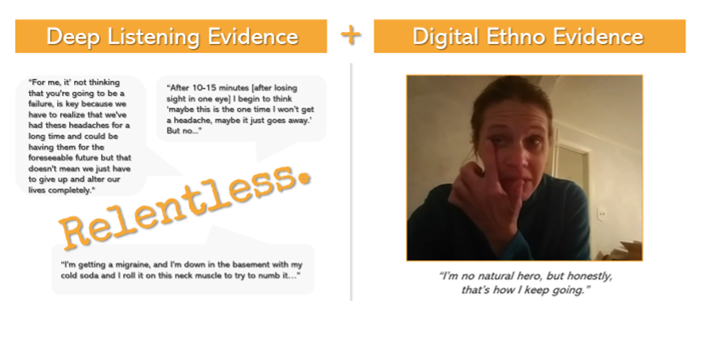

“Relentless”

The brand Lilly’s new migraine pain medication… The challenge was to propose a go-to-market campaign for Lilly’s new migraine treatment for patients who suffer four or more attacks a month. The brand promise was “more migraine free days”. The audience insight the brand team shared was that these people were resilient in their ability to bounce back from migraine’s attacks.

Deep Listening program We developed a range of targeted queries to scour the social ecosystem for evidence of humans sharing stories, seeking advice and supporting one another in their battle against migraine. Our analysis articulated two insights – ‘quiet armor’ and ‘relentless’ – both of which we tested as descriptive territories within a sequenced digital ethnography study.

Digital Ethnography program Our digital ethnography study observed ~15 migraine patients who suffered at least five migraine headaches a month. We asked each to respond via video, text and image to the two territories we developed from the deep listening study.

The results The brand team’s insight of resilient certainly wasn’t wrong, but we discovered a more potent insight lurking beneath it – relentless. Resilient describes someone who’s developed a set of defensive responses to warding off her attacks. Relentless describes a migraine warrior in near-constant battle mode driving away her pain with an almost religious zeal. The creative strategy and platform we developed was – be relentless, help is on the way.

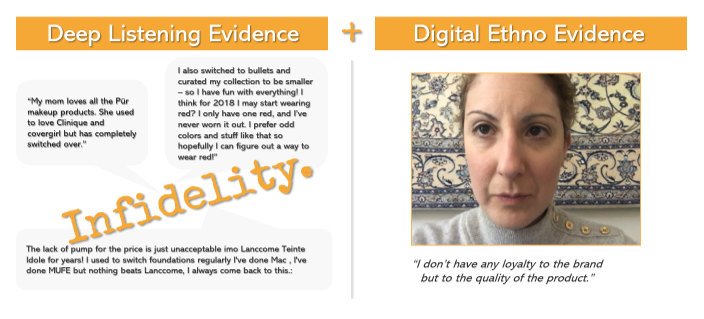

“Infidelity”

The brand NARS briefed us with two big problems, customer acquisition and retention. With a market share under 5% for key products, their insight was that customers were not loyal to cosmetics brands as much as they were to individual products. The brief was to solve for this by building a loyalty program that could drive first time product discovery resulting in escalating repeat purchase.

Deep Listening program We developed a deep listening program with a language taxonomy focusing on the use case of cosmetic product experience, advice and recommendations. We articulated two insights – ‘cheating’ and ‘share of me’, both of which we tested as territories within a digital ethnography study.

Digital Ethnography program We fielded a program with ~25 cosmetics users and asked each to respond via video, text and image to the two territories we developed from the deep listening study.

The results Our investment in deep listening + digital ethnography research deepened the client’s ‘not brand loyal‘ insight to cheating in our deep listening and then further in our ethno towards infidelity – a territory of human desire sizzling with ownable frisson. The digital ethno research also validated our deep listening’s share of me insight, and this fueled our strategy for a CRM program focused on earning more ‘share of face’, increasing product trial and usage in an escalating coverage of lips, eyes, cheeks and brows.

A different kind of brand

Over the past three months of global pandemic there’s one thing everyone agrees upon – the world will be a different place on the other side of this battle with the corona virus. One of those changes might be the very nature of brands.

Evidence of this, for me, is already at hand. About three weeks into lockdown I realized I was unfollowing and unsubbing brands on social, email and Youtube with impunity. This wasn’t a conscious strategy, I just found myself blocking out more and more obvious noise from essential signal. The new rules of lockdown somehow brought with them a fresh clarity about what matters.

For the past twenty years we’ve all been debating whether it’s possible for any business to credibly claim demonstrable and authentic purpose. In Q1 of 2020 I think that debate moved quietly into the moot column.

Purpose, if it passes the new highbar test of not being bullshit, will be entry-level table-stakes on the other side of Covid-19. Meaning (as it pertains to real value in my life) and action (how a brand behaves in the world) are likely to become the only real test of whether anyone cares about who we are, what we make, and why we matter.

We’re gonna need a deeper insight

This creates an existential problem for the majority of brands in the world today. A problem they won’t be able to advertise their way out of. A different kind of marketing, and by this I mean nothing less than a different way for a business to behave, will be required. I’m betting those old pre-pandemic insights are probably not going to be much good to us in this brave new world.

Here in late May 2020, every single brand manager on the planet is squinting through the Zoom haze, puzzling what will happen for their brand in that unknowable world awaiting us all up ahead. To these marketers I suggest a simple if scary truth: you’re gonna need a deeper insight. A frighteningly deep insight about the human condition which your brand solves for, might be the single most powerful factor in creating and sustaining extreme competitive advantage in a world no brand manager has ever had to imagine.