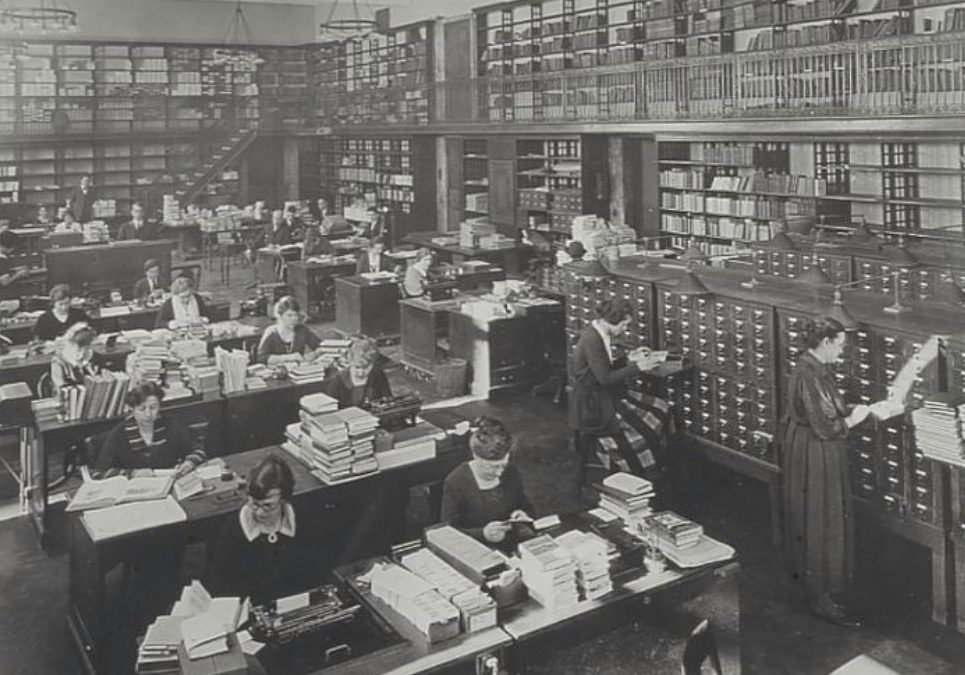

The Picture

Browsing Reddit I stumbled upon this image of Room 100 of the Central Building in the New York Public Library. Its catalog details are dateless but the clothes, hairdos and office equipment seem to place the moment in the teens of the 20th century.

My New York chauvinism presumes this was state-of-the-art in the go-go days of early modernity. Room 100 would have been its brain, the system’s central processing unit with its card catalog system indexing a vast database of manuscripts, objects and books.

I count thirteen women and six men, a healthy two-to-one ratio. This suggests, anecdotally, the early days of information management system culture were dominated by female knowledge workers. Then I see a guy, that stern-looking guy in the back. His hands clasped behind in the classic pose of ready reproach. This is the boss. Some things in business change more slowly than others, and males dominating the management class remains infuriatingly one of them.

We Were Warned

Aldous Huxley, writing in 1932, imagined his Brave New World of techno-dystopia as a huge card catalog index. He might have guessed wrong on the storage media, but his prediction betrays an insight: library sciences in the early 20th century was the innocent precursor for the Wild West information economy we inhabit today.

So, how did we get from that mostly girl-powered Room 100 to the brave new marketplace of facial recognition and black-box algos? In less than a hundred years we galloped from an open-access, community-financed, human value-add information culture to something Huxley basically nailed: a violent chaos of data energized by the cold logic of value extraction – a surveillance economy.

Boys and Their Toys

History’s short, brutal arc from our image above to that touch-screen you’re staring at this very moment has a defining characteristic – phallo-technic. An insurgent whiff of testosterone infuses every leap beyond the analog. Turing’s machine thinking starts sparking early innovations like Colossus, the mighty Allies’ crypto-breaking war machine. From there, the guys blast genius paths to stored memory on tubes instead of cards, and by the 60s they came up with microprocessors and CPUs. Big businesses formed around these break-throughs – companies like Sperry Univac, IBM and Intel all laying claim to the emerging frontiers of cutting-edge tech. Then the 70s happened, and the soon-to-be unholy trinity of business, government and academia spawned the defining product Eisenhower warned us about – Messrs. Cerf and Kahn’s development of TCP/IP and the birth of ARPANET. Recognizing early they had a naming issue, somebody in the vast military-industrial complex had the branding smarts to re-christen their new everywhere machine the Internet.

The battle matrix for humans versus machines was locked and loaded. If only there was a simple way to connect it all. Thinking through the problem of what regular people might be able to with all those connected servers, Tim Berners-Lee came up with the protocol for the World Wide Web. The lowly but lovely browser was born and released into the early 1990s world with the promise of a “free and open” web for the world.

And so began the most fertile, frenzied fifteen business years the planet has ever known. A handful, you guessed it, of guys puttered their way from garage labs to an almost total takeover of the Web. Today was born, the state of human affairs defined dystopically by the FAANG-ilization of everything. Huxley, dude – how did you know?

Theft as Gift

If there’s a key to understanding how we got here it’s the human data-theft at the heart of our devil’s bargain with the FAANG/BATs* (*adding the emerging Chinese tech conglomerates Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent.) A theft calculated by the imbalanced exchange of our data for their “free” services, utility and content. The swindle sealed by a brilliant if insidious deception, that what was sensed as newfound control turned out to be full frontal surrender.

This human data theft premises, privileges and permissions the dominating platforms to treat this new connected culture lab as their shareholder piggy bank, ringing up billions in $s, ¥s and €s each hour with its super-efficient violence of value extraction by-design.

Capital’s OS

There’s nothing new about the insight connecting the human male with aggression. The history of everything – science, philosophy, art, sport, invention – has always been told through the muscular narrative of men on the march. Business and its platform of capital perhaps even more so. But the 20th century’s technological advances, along with their owners, sponsors and profiteers were definingly male, fueled by states, their militaries and compliant academic accomplices.

Marx in all his prescient insight about how capital morphs and snakes through a social system couldn’t have predicted such omnipotence. No one (if only Huxley’s insight was more economic) could have imagined how capital might behave when unleashed across the digitally collapsed frontiers of nations, markets and human autonomy itself.

But here in the teen years of the 21st century, capital has found its most perfect operating system. Essentially owned and operated by the FAANG/BATs, finally exceeding states’ powers to regulate by cutting them in on the deal. The merits seemed obvious, for a few cycles. But now the darker downsides unsettle, even if muted by the seeming benefits. All we have to do is lean forward, accept the terms of service and enjoy the pleasing haze of surrender. Or not.

Fork You

One of my more unlikely sources of insight is Audre Lorde. In the late 70s, in her call-to-arms for a broader reset of culture, politics and governance she suggested, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”. Lorde added a caveat to her provocation – “in the long run, anyway…”. I take her qualification as inspiration for an alternative path to our shared futures together.

Lorde understood that, in the near term, sometimes the fastest and most efficient way to ignite change was to borrow from the master’s tool-box. So, from our reigning overlords of the technosphere I borrow a term – forking. Originally coined by application engineers working in the early Unix operating system, it describes how a system makes a copy of itself in order to launch a new program or procedure.

It’s useless to ponder what if we hadn’t succumbed so completely to the current techno-economic regime. But it’s not crazy to suggest an act of shared re-imagination about what’s next – and doing something about it. Given the choice and taking the chance, ask ourselves what a more equitable human fork beyond this replicant economy might look like.

Look at Me… I matter!

Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek lay equal claim for musing, “it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”. We won’t be solving for capitalism, but it’s certainly within our imaginative grasp to re-engineer a fresh fork in the fabric of our shared technosphere.

Our first leap together is the toughest, but everything depends on it. We must re-imagine a reward incentive to replace the predatory value extraction at the heart of the current model. Imagination without insight is an empty exercise. The stakes are too high and the opportunities too sweet. We arm ourselves with an insight grounded in the ancient core of human need: recognition and affirmation.

This is the essential human insight driving our behavior together since we sat around communal fires 50,000 years ago to tell stories and share things like food, heat and protection against the forces from without. It’s the insight we’ve been baking into our creative briefs for a more radical marketing for the past twenty years.

It’s also an insight we’re all intimately familiar with, given our newfound togetherness on socially connected devices. Whether you’re a lurker, a poseur or somewhere in between, that feeling you get when someone likes your lunch picture or comments on your pithy comebacks is a pleasing if minor reward. A gift minted in a scalable social currency of affirmation and recognition.

If we need an insight to spark our imaginative leap into a different future of everything, I’m going with – “Look at me… I matter!” The challenge remains what we do with it to disrupt the disruptors out of their ubiquitous ownership of our 24/7 lives.

The Big Lie

Our primary solve for applying this insight is cost. The cynical lie at the heart of the surveillance economy is that the companies who give us all this free stuff – image storage, social connectivity, email and massaging, document management, navigation tools, video services – need to pay for them with advertising.

I’ve been in the global advertising and marketing racket for over thirty years and I can tell you, as we say on Madison Avenue, this is absolute bullshit. From the radio soap operas of the 1930s through to the sitcoms of the current twilight of linear TV, the default economic model was to exchange content costs with eyeball reach.

But advertising is an increasingly moribund model when it comes to getting and keeping customers. Brand marketing teams, agencies, publishers and broadcasters have known this for the past several years and are frantically trying to figure out alternative models. Don’t expect what they come up with will have you the human at the heart of its value equation.

Note well: if we’re imagining a more equitable human technosphere, someone will need to pay for it. The shareholders of the FAANG/BATs – full disclosure that includes me – aren’t candidates. We, and that includes everybody, will need to be ready to offer up some value in exchange. This new currency of exchange, unlike the attention we spend under today’s regime, will be something quite different.

Identity and Attention

Under the dominant rules the most valuable asset we control is not our attention. It’s our identify itself.

In the past fifteen years Google, Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, Apple and LinkedIn (the shortlist) all have aimed for a lock on owning and managing our identity. Each developed APIs and competed for publishers to offer their credentialing service in return for reducing the friction of visitors to their sites or apps to register. This was a brilliant strategy for aiming to “own” human identity on the Web. The winners would become the custodians of our identity, allowing them to monetize our attention and continue gathering our personal data trails, even when we were off their sites and networks.

We underscore this founding and enduring connection between identify and attention, and the pair’s critical role in the business model of platform value extraction. Pundits coined the benign term the “attention economy” to sugar-coat the brutal mechanics of the emerging surveillance economy. But what we thought we were so freely exchanging wasn’t really our attention. That was simply the metric (see views, impressions) of their very last-century media model. What this economy was actually based upon was the signs and manifestation of our identity itself – our behaviors, our transactions, our attitudes and our fears, our desires and our demographics. Our human identity data serving as fuel for all this perfidy.

If identity is how we signal our authentic and autonomous presence, attention is merely just one of the things we do with it. With our forking leap grounded in the human desire for connection and affirmation, human identity is a critical first principle. Our digital, just like our IRL identities, must be integral, persistent, authentic, privately and personally owned and controlled. Unlike the current mess we’ve surrendered ourselves into, it must be ours. Identity has been the golden goose of the surveillance economy’s value model. We want it back.

For several years infosec geeks, technology activists and a handful of marketers and payment solutions companies have been talking about the personal information economy. There is much to be inspired about here. But we can’t kid ourselves about the daunting task of challenging the profit at stake in the walled gardens of the hegemonic platforms.

The Diamond District

To the platforms, attention was always a zero-sum competition. Ever wonder why links are rare on Instagram or why those redball notification counts are so addictive? The platforms engineered everything they could to keep you on their sites and apps when you got there and get you back soon and often when you left.

There’s a problem with this idea about attention being zero-sum – it isn’t. Yet, in order to more fully monetize our identity through our attention, the platforms and the complicit brands they’ve duped all had to believe the same things about human desire, value exchange and the very nature of competition. They got all three wrong.

I teach a graduate course in Competitive Strategy at NYU. On the 19th slide of tonight’s first lecture deck are three words in 90 point type – FUCK THE COMPETITION. The insight here is one you won’t get from traditional business theorists (99% men by the way). They advise we obsess over the competition, so to better annihilate them. This defensive zero-sum thinking informed the product, interface and technical design strategies for all the big box platforms. Hold that thought.

For evidence to support my profane advice, I suggest my students take a walk down 47th Street between Sixth and Fifth Avenues. If you know Midtown New York you know that block is crammed with jewelry stores selling ~$400 million worth of diamonds every day. Each one of those shops is competing with each other. Observer’s intuition tells us this is dumb. Why would all these competitors within a single category put up their shops next door to each other. The answer is because this is where the customers are.

Each of those stores is forced to compete for customer attention, dwell-time and purchases in one of capitalism’s most Darwinian exercises imaginable. Here’s the insight: this commercial system is the anti-thesis of zero sum. Everyone’s a winner, but mostly the customers who know exactly where to go, how to compare and who to buy from when they’re diamond shopping.

Better Business Building

The key that connects our forking strategies to these gathering insights is value. Our brief is bold: how do we enable humans to come together with each other in their shared worlds – cultural, social, commercial, political, economic, aesthetic – in moments of mutually satisfying value exchange. And, when the moment presents, get and keep them as customers.

I have a disclaimer which my cowardice can no longer contain. I’m a selfish business strategist (if a slightly more interesting value marketeer). My aim of strategic attack remains true: mine and articulate fresh insight powerful enough to be transformed into value. Value first for humans and then, the selfish part, the businesses who hire me. My call for forking radically from the predatory platform models of today isn’t altruistic. It’s good for business. Better business, different business. Sustainable and organic business.

Recent business history is rife with inspiring cases…

- One of history’s most commercially disruptive business models exploded at the heart of technology itself, the open source software initiative. Launched in 1998 it was intended to foster a community of creators, software developers, around the principles of free speech. The software wasn’t meant to be free, but its collaborative creation and distribution was. Within ten years of its founding the reigning software industry incumbents Microsoft and SAP were forced to succumb to variations on its themes, or become marginalized and irrelevant.

- Wikipedia was founded in 2001 on the same principles of collaborative value creation, or in the words of its Wikipedia entry (as meta as you wanna be…) – “based on a model of openly editable and viewable content”. Within four years, independent comparative reviews of the quality and extent of its entries against the dominant incumbent encyclopedias essentially put those publishers out of meaningful business.

- Bandcamp is another business model based on the refreshing new rules of respectful mutual value recognition and exchange. It’s counter-intuitive post-platform axiomatic confounds Hayekians fully: the pricing posted by musicians for purchasing their music is set as a floor, and 40% of the time customers choose to pay more. Music and media critic Steve Smith suggests Bandcamp’s growth and popularity is due to its “responsible and ethical business model more equitable to artists than any other retailer of comparable size, but also a savvy grasp of social media’s power of peer-to-peer persuasion, implemented through public-facing “collections” meant to function as virtual record shelves to be pored over and emulated.”

- Another jewel in the crowd of emerging better businesses is GitHub. Launched by two developers in 2008 it was acquired by Microsoft in mid-2018 for $7.5bn because, well, the Internet… More specifically, like other companies forged upon the exponential power and value of community, GitHub offers its code repository and hosting services absolutely free. As long as you’re cool with all your work being public. This is a lower barrier than you might imagine. According to this paper analyzing its business model, “GitHub currently hosts millions of free repositories, including many powerful projects like MySQL and Ruby on Rails used by GitHub themselves to power the platform.” Italics added and you can see why.

Each of these modestly alternative businesses share at least five key characteristics, distinguishing them from the reigning predatory models.

- They leverage community to scale contributive value through collaboration.

- The rewards reaped by all participants are either symmetrically aligned, or equably unbalanced to the mutual benefit and happiness of all involved.

- The core behaviors of value exchange are essential public acts of private production.

- The exchange of products and services generate uniquely exponential surplus value. One plus one isn’t three – but, potentially 3 million (see characteristic number 1).

- Although none rely on decentralized technology a la blockchain (that’s another chapter…), both trust and authority exist within and emanate from the contributive crowd.

It’s Tomorrow Again

In 2009 Google sent a crew of corporate flacks into Times Square to ask people “what is a browser?”. The self-serving video they promoted elicited the desired response. People thought of their browser as their search engine. Lol, what sweet dear idiots. In retrospect, Google’s stunt seems more strategic than mean-spirited. Exactly a year before wading into Times Square, Google launched their own web browser Chrome, and it wasn’t yet ripping commanding market share from the then dominant Microsoft Internet Explorer.

Google’s insight from their video was used to ignite a market-share grab that soon proved those poor misguided people were actually right. Today, Google enjoys almost 70% of the browser market and over 90% of the search engine market. And we don’t even have to trouble about going all the way over to google.com to search — just pop those search terms into your browser’s URL box. Combining these two interfaces and offering both ‘free’ remains the founding act of the extractive surveillance economy. An economy that generated about $120 billion for Google in 2018 – nearly 33% of all the advertising income cashiered globally.

This sort of commercialization of online attention through the primary entry-point into our connected world probably wasn’t what Tim Berners-Lee had in mind when he founded the W3C as a not-for-profit organization in 1994 to release his invention of the World Wide Web to the world, “available freely, with no patent and no royalties due.”

But it most certainly was a factor inspiring Berners-Lee (TimBL to the digerati) to found another organization, the World Wide Web Foundation in 2009. At the time, he announced the move as a necessary step to, “advance the Web to empower humanity by launching transformative programs that build local capacity to leverage the Web as a medium for positive change.”

TimBL was making a point. The “positive change” he had imagined was not about the unimaginable market cap realized by the surveillance platforms who have been monetizing his invention since he went all pay-it-forward and gifted it to the world “free” twenty years earlier.

I say we have a winner. Our pivot model is Tim Berners-Lee and his founder’s intent for what was to be done with his invention called the Web. We don’t need to fork from the chaos of extraction dictated by the FAANG/BATs of today. Philosophically and strategically we aim our imagination and stake our fork at the same ethical, technical and social location Berners-Lee set the damn thing free in the first place.

Real Feels

Here on the edge of the 2020s the digital fumes of a pervasive and violent system of connected platforms sicken our lived experiences on the planet. Recall the data theft and value extraction at the heart of its formula for exchange. We’re proposing to subvert, reject and eventually replace that life-negating technosphere with the more touchy-feely kumbaya model as imagined by Berners-Lee and his fellow do-gooders from the World Wide Web Foundation.

Go ahead, place your bets. But then hold my beer…

Reconsider the picture atop our wandering manifesto. Imagine yourself one those primeval knowledge workers. What got you going each day? My guess is it was a passion for knowledge and a love for sharing it. Here’s another question – don’t you think they would’ve wildly embraced Berners-Lee’s quixotic quest to “empower humanity by launching transformative programs that build local capacity… as a medium for positive change”?

Me too.

The reason 40% of music purchasers on Bandcamp pay more than the musicians ask is because they love their music and it makes them feel good to pay more. They will never forget that feeling of munificence, of generous willful contribution. It makes listening to that music, and the emotional relationship to its producers, different and special.

How about those developers giving their code away on their no-charge GitHub because, what the hell: maybe someone can improve it, do something with it I might not have done. Better together rules.

How about all the thankless hours nameless Redditors spend moderating their subreddits or Wikipedia editors compete to nurture their entries. I imagine they’d all say it was time well-spent.

We improve each other when we share and give. And that, if you’ll pardon the warranted exuberance, feels fucking great. It’s a little bit vain sure. It’s a little bit self-serving, adding to the bank of our social currency among communities that matter to us. Communities of people – customers, employees, partners, clients – that matter to my happiness.

There’s a final insight we can lean on to inspire us to start building and sharing things differently, whether it’s products, services, companies or communities. Importantly, it’s the same insight about why we spend so much time on social networks and what we get and give in return. Belongingness. We gather in these communities to affirm our place in the world. To prove to ourselves we matter. We belong there, here among the like-minded, like-employed or like-impassioned.

Passion. That’s the thing we’ve got to bake into the core of our replacement formula for value exchange. The passion to create, to nurture, to add not subtract to something of minor meaning in the world. Feelings, real feelings, are the domain where the rewards for this work are both sown and reaped.

But is it possible to imagine, never mind develop, a candy brand, or clothing brand, a soap brand or a pharmaceutical brand inhabiting the marketplace under such a feeling-based regime? Well that’s the job at hand. So we’d better figure it out.

For inspiration, we take one more loving look at those long-gone library staff. They showed up to contribute. Their work gave them worth. Their service was of a particular and very special value. Their passion for helping knowledge sustain and spread was a potent and positive force in the community of their customers, users – humans.

Not bad poster-kids for a brazen fork towards a world of humans and brands – and the technology that connects us all.

This article is adapted and excerpted from Kennon’s upcoming Radland: Battle Guide for the Marketing Revolution to be published in the Fall of 2019.